Adopting or Adapting?

April 5th, 2010

Those who may have missed Anya Kamanetz’s DIY U: Edupunks, Edupreneurs, and the Coming Transformation of Higher Education got several chances of late to get at least a sampling — e.g., her contribution to the “debate” staged by the NY Times under the title “College Degrees Without Going to Class,” the recent interview of her in the Chronicle, and her “Adapt or Decline” piece in Inside Higher Ed. (Arguably the best introduction to her thinking, short of the book, is an extended video of her holding forth for half an hour.)

Inevitably, what she sees as an opportunity — to cut costs and forge new paths given the availability of open educational resources (OER) — seems a danger to others. David Wiley says in a recent blog post that if you turn students “loose with links to some OER and expect good things to happen for more than 5% of them, you’re just off your rocker.” Similarly, Michael Feldstein, in his blog E-literate, holds that most “students are not autodidacts,” and so it is not clear to him that “the blossoming of open education for their more fortunate peers will do anything for them other than suck the much needed funds out of an already badly underfunded education system.” These takes exasperate Stephen Downes who thinks they confuse the baby with the bathwater: “The reason we have so many students who are utterly unable to learn for themselves is precisely *because* of corporations and institutions.”

To circle back to Anya Kamanetz, her “Adapt of Decline” imperative is a slightly more evolutionary version of “Do or Die.” But it’s addressed to institutions. And the people who, well, people those institutions have their own spaces in which to move and their own decisions to make. That would be a good reason to note that Anya Kamanetz’s imperative is, as the Chronicle article notes, a “moral imperative” — to give the full headline “Anya Kamenetz Invokes ‘a Moral Imperative to Cut Costs’ With Technology.”

This might be a call for some personal if not institutional adaption. ‘Tis the season for textbook adoption. It could be interesting to break the mold, go for something new — digital content, open access publications, e-resources from the library, things you can link to rather than have your students buy. It’s not a giant step. But it’s a step. If your CUNY faculty, your university is already taking steps to save your students money on texts. Why not go the institution one better?

Print Books and Digital Content

March 12th, 2010

I want to recommend something I recently stumbled upon (literally: using StumbleUpon, I found something praised on Slashdot and tracked it down to its source): misleadingly titled “Books in the Age of iPad” — my first thought, in the wake of all the iPad hype, was “I don’t need this” — it turned out to be a very thoughtful (and, for me, revelatory) meditation by a publisher and designer on what the possibilities posed by digital content mean for “for books-makers, web-heads, content-creators, authors and designers.” As I read what Craig Mod had to say, I thought of a critical audience he didn’t mention: faculty.

He begins with Maximum Provocation:

Print is dying.

Digital is surging.

Everyone is confused.

GOOD RIDDANCE.

But what he is saying “good riddance” to is definitely not books. It is to the “disposable books” (his term) — books that don’t need to be books. His other term for this is “formless content” (content whose meaning is not determined by the container) as opposed to “definite content” (content whose meaning would change if the container did).

Complicated by further distinctions and examples (laid out in beautiful design, by the way), this is of course not an absolute distinction, but it is definitely a thought-provoking one. For those contemplating CUNY’s eBook RFP, for example, it may help to cut through all the confusion about devices and formats and so on. When we discussed that last week at the monthly meeting of the CUNY Committee on Academic Technology (a private group on the CUNY Academic Commons as well as a University committee), I was hearing considerations that to some extent crystallized as I read Mod’s piece. What among the material we would have our students read or look at is formless and what is definite content? Remember that the latter can be digital content, not just books. And there are still odder compromises and symbioses. When I first started using Project Gutenberg, one of the attractions was using digital means to create historically accurate facsimiles of literary texts as they originally appeared.

Of course, I’m speaking from vantage point of my (erstwhile) discipline, and I think one of the great questions here is how this distinction would play out at different kinds and levels of instruction. For me, the critical thing that Mod’s piece reinforces is how technological change almost never confronts us “either/or” choices, but with “both/and” options — always more complicated. Just as the VCR and DVD did not kill movie theaters (but made us all think more about what to watch where and when), the opportunity to assign digital content as well as traditional print textbooks has ramifications that are going to require thought, and what Mod has to say may be of some help in thinking them through. It certainly seemed so to me.

Dispelling Myths about Online Ed

February 24th, 2010

I need to be careful, and not just because one person’s myth is another person’s religion. I was motivated to post on this because of a commentary piece in the Chronicle of Higher Ed titled “Combating Myths About Distance Education.” My first reaction to this was to roll my eyes, thinking “Oh no, not again.” One of the great myths is that “distance education” is an appropriate term for online education (and not, increasingly, a misnomer). But an even greater myth is that whatever-you-call-it is easy to define (and so to combat or dispel whatever one regards as myths about it): all you need to do, according to this myth, is tell the truth, and the scales will fall from the eyes of the unbelievers (or believers, depending on your perspective).

Well, the truth is that things get more blurred all the time. Is online ed about distance or local outreach? (Increasingly, it’s the latter.) Is the true point of contrast face-to-face? (Then what about the single biggest growth area, hybrid or blended learning?) Is it all about asynchronous interaction — a sentiment so widely shared at one time that it made sense to call the biggest journal in the field the Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks? (Then what about all the work with synchronous interaction, especially in the very course management systems and programs that used to be wholly asynchronous?) And then there’s the fact that the Chronicle of Higher Ed has never been friendly to online ed, loving to invoke specters of diploma mills, spy cams, and faculty being automated out of existence, all of which is just plain silly.

So I didn’t expect much from the article. I was pleasantly surprised. I can’t say it was full of revelations, but it resisted easy generalizations and stereotypes. The real gripe of the author, a librarian at Yale who teaches a variety of library and literary studies courses online, is that he gets no respect — senses that online ed people are the Rodney Dangerfields of higher education. Memorably, he noted that one “big state university” he taught for “does not even acknowledge its online instructors as members of the faculty on its Web page. In the department’s eyes, I am, like Pinocchio, not a ‘real boy.'”

There were things in the article I disagreed with, inevitably. For instance, he draws an easy distinction between undergraduate and graduate instruction that, as I’ve argued elsewhere, is another thing that’s blurring, and blurring because of online ed (and what access to the internet does to the need for instruction as “information transfer”). Inevitably, to make his point, he restored to generalizations, even stereotypes.

So what amazed me most — what motivated me to go online and post about this — was one of those generalizations I did not take exception to. In fact, I’m not sure it is a generalization with exceptions — which, of course, violates the general rule for generalizations. In contrasting online with face-to-face instruction (and the possibility, even invitation, posed by the latter to let the student sit there passively in the classroom), he says that when students “take good courses online, they are required to be full partners in their learning process.” I realize you have to stress that key word “good” there, but, if you do, that holds — and so does the contrast if you insist you’re comparing it with good F2F instruction: there are simply too many barriers to full partnership in the classroom, like the impossibility of everyone answering a discussion question almost any time one’s posed (a standard expectation in online instruction).

So I came with low expectations, but seem to have found a real touchstone. Or should someone tell me to take my rose-colored glasses off?

Thoughts on Hybridity

January 4th, 2010

The most important thing to say about hybrids (partly online, partly in-class courses) I said in my last post: there must be fairly stable and widely shared expectations about them, especially from the students’ perspective. Things like how they’re scheduled (and impact on student and faculty schedules) can’t be unreliable or erratic. Yet the prospect hybrid courses should present puts the cart before the horse: the first thing to consider is what would motivate hybrid instruction in the first place.

Why have hybrid courses? There are a host of reasons, from the personal (the convenience they should mean for both faculty and students) to the institutional (the conservation of classroom space, perhaps even the acceleration of time to degree). But the ones I want to stress have to do with teaching and learning per se — what instruction (hybrid or otherwise) is presumably all about.

Perhaps no one ever did more to get at what mattered most in teaching and learning than Arthur Chickering and Zelda Gamson, who, in 1986, summarized decades of educational research about which kinds of teaching/learning activities improved learning outcomes; they distilled that research down to their famous “Seven Principles for Good Practice in Undergraduate Education.” According to them, good practice in undergraduate education

- encourages contact between students and faculty,

- develops reciprocity and cooperation among students,

- encourages active learning,

- gives prompt feedback,

- emphasizes time on task,

- communicates high expectations, and

- respects diverse talents and ways of learning.

It’s not hard to see how hybrid instruction, offering new/online forms of interaction and communication (even as it reduces “seat time”) helps to address these. In fact, that’s precisely the reason that Steve Ehrmann worked with Arthur Chickering to apply these principles to online and blended learning in “Implementing the Seven Principles: Technology as Lever.”

That these principles apply to online teaching environments as well as classrooms is obvious. What is perhaps less so is that they apply differently. Online interaction or communication is not the same as that which occurs in classrooms — think, for instance, of how online discussions allow everyone to contribute in ways that would chew up too much time in the classroom — and that has to be taken into account in planning online and hybrid courses. Since online instruction has to maximize its advantages (the reflection allowed by asynchronous instruction) while minimizing its disadvantages (the loss of the immediacy and spontaneity of the classroom), it has become common to think of hybrid or blended learning as the “best of both worlds.” This is such a popular way of invoking the possibilities posed by blended or hybrid instruction that we shouldn’t be surprised to see it used, not just once or twice, not just three times or four times, not even five or six or seven or eight times, but nine times, ten times, and more.

“Getting the Best of Both Worlds” was in fact the theme of the 2009 Sloan-C Workshop on Blended Learning and Higher Education some of us were involved in (and no, it’s not one of the hyperlinked “best of both worlds” instances above). Of course, “best” may be in the eye of the beholder. Determinations of how to get “the best of both worlds” will likely vary by instructor, by discipline, by kind and level of instruction. And so it may be still more useful to mention the theme of that same annual workshop from the year before: “Blending with a Purpose” was also the title of the keynote presentation by our own Tony Picciano. A version of that presentation is available on YouTube. Tony also edited a special issue of the Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks on blended learning that features another version.

I recommend both versions to all who are interested in hybrid courses, but above all I recommend what is at the heart of both, nicely encapsulated in that phrase “blending with a purpose”: academic program and course goals and objectives should drive the approaches and technologies used in hybrid courses. Is the overarching goal of “going hybrid” to increase interaction among students? to get them to say more in response to course content than classroom time would allow? to appeal to a variety of learning styles? to foster collaborative research? to make instruction writing-intensive? Whatever the big reasons, and these barely scratch the surface, the great achievement would be to make the blending of online and in-class instruction purpose-driven, goal-oriented. Easier said than done, no doubt, but then the point is how much easier it would be to start with the pedagogical goal(s) in mind.

Talking about standards (re blended learning)

December 3rd, 2009

The term “standards” is radically variable, like Schrödinger’s Cat, dead or alive depending on who’s looking in the box when. It’s hard to say you’re against standards, but if you’ve been around the CUNY block as often as I have, it’s also hard not to suspect that talk of standards is some kind of code for closing the door on students or regimenting faculty or something still more nefarious (as if anything could be).

So, for my own sake, I have to take pains to say what I’m talking about when I talk about standards, particularly as applied to blended or hybrid (partly online and partly in-class) instruction. In talking about standards, I’m not talking about standardization. This is not about everyone being on the same page, much less the same platform. Teaching styles and strategies and purposes and content differ way too much for that in any modality. Ditto the technologies involved (emphasis on the plural).

What I am talking about is standards as shared expectations — knowing what we’re talking about when we talk about blended or hybrid courses. And I want to be clear that “we” are really not the people I’m primarily interested in here. The critical thing is that students know what we’re talking about when we invite them to take a hybrid or blended course. They should know what this means to the scheduling of their time. They should know what the potential challenges and advantages are. They should know that they’ll be going on line to do more than just look at stuff between class meetings.

I realize this already constrains some faculty more than they would want to be constrained. Potentially, a hybrid course could be located at any number of points on a spectrum of mixtures of online and in-class. An instructor could decide at any number of points (like the week before) when to schedule some online activity or demand that students show up for a face-to-face session. And if this keeps the students uncertain of what is happening when and where, the instructor so inclined could say it also keeps them on their toes. This mix-it-as-it-comes approach can also be justified as the necessary cost of pedagogical experimentation, of finding just the right combination of online and in-class.

I think that approach is inexcusable, and I want to say that unequivocally. If hybrid or blended instruction is something we are going to do on a large scale, there can’t be endless variability and uncertainty, especially from the students’ perspective. In a game like that, only the professor wins, and at some cost to the students. Academic freedom does not entail the right to do students harm. What’s more, if we are going to take academic freedom seriously, we need to acknowledge that good pedagogy is, to a considerable extent, in the eyes of the beholder. Let’s face it: finding just the right mix of online and in-class interaction will be a never-ending experiment, particularly if we consider differences across disciplines, changes in technology, and so on.

We owe the student some stabilizing principles. There should be clarity in scheduling. There should be a commitment to interaction, both in class and online. The one thing that should be never-ending is the feedback loop.

In writing instruction, there’s the term “enabling constraints” — a coinage of CUNY’s (Queens’) own Judith Summerfield. Students struggle less with an assignment that gives them a sense of form and audience (like writing a letter to someone they know) than with one that simply asks them to write something/anything; obviously, those constraints still leave so much up to the writer.

I think we need some enabling constraints for blended or hybrid courses. I think they should be roughly a 50/50 split of online and in-class. I think the meetings should as regular as standard courses (but less frequent because of trade-off in online time). I think we have to insist on online interaction between student and teacher and/or student and student (and not just student and content). I think we should get hybrid courses defined clearly in course schedules, and in time so students can see that as they are register.

Some people will think these are reasonable assumptions. Some will think they are abrogations of faculty rights and of the need to experiment. I would like to hear from both, but especially the latter.

Not wanting to end on a semi-pugnacious note, I’d encourage you to check out an announcement in Tony Picciano’s blog on an excellent upcoming national conference on blended learning. And everyone interested in blended learning should have and read Evaluation of Evidence-Based Practices in Online Learning, a meta-analysis published under the auspices of the US Department of Education. The gist is that, in terms of learning outcomes, online learning is marginally better than classroom based learning — but blended learning is significantly better. I can think of no better justification for faculty buy-in than that.

What We Need Is What We Have (Part II)

October 21st, 2009

Part I was my first post on this blog to “escape” comment and my only one to explicitly invite comment, so I’m on my own here. It may well be that the expectation is that I should finish what I started, not leave things hanging. Very well.

My basic point in that previous post was that, contrary to one explanation for why online learning has plateaued, I don’t think the re-ignition of the growth in online and blended learning awaits some new technological innovation we don’t have. And I say that despite seeing, just yesterday, a reaffirmation of that position in the Chronicle of Higher Ed’s “Wired Campus” blog: “Online Programs: Profits Are There, Technological Innovation Is Not.” Stepping around the swamp of speculation about online learning as a cash cow (think how many ships of foundered on those shoals), I’d say what we’re really waiting on is a fuller understanding what of we have in online teaching and learning now, at least potentially.

That understanding, I would aver, is not unlike the understanding western civilization had to move to in its last great technological revolution (using the term as it should be used, to signify real upheaval and overturning). When, in the mid-1400s, the advent of the printing press meant that, not just the putative Word of God, but the words of Aristotle (and a host of other past luminaries) could be put in the hands of the literate laity, professors were as frightened as clergy that they were being superannuated, “automated” out their jobs as mediators of truth, learning, information.

That turned out not to be the case, of course, though it took centuries of growing literacy (we’re still working on that) to get the full sense of what the change was (and was not). Books didn’t replace teachers. They enabled teachers, empowered teachers, required teachers.

Ditto technology. It has made faculty more important than ever before. Their job was never (just) information transmittal. Books would have sufficed for that. But what we’re after is not information, but knowledge. Knowledge is the fruit of interrogation, interpretation, application, criticism, synthesis. You need teachers for that. They have plenty of work to do. And technology helps. Arguably, it helps most of all by getting us past the idea that the transmission of information is the great goal.

Nobody puts this better than John Seely Brown, particularly in a keynote talk he did at the University of Colorado’s 2005 Teaching with Technology Conference. He is all over the place in the talk, making fascinating observations about how amateur astronomers are outdoing their professional counterparts, partly because they engage in more online collaboration. I might have missed the key insight at the end if I hadn’t been listening to this as a podcast (and during a long run). He suggests that we are moving from one model of education, particularly college education, to another.

The old model is a one-way exchange: people who have information give it to those who don’t have it. This is basically a packaging operation: wrapping up thought (in lectures, courses, books) and presenting it. As JSB reminds us, this is not the only model of education. He notes that the model of graduate education was always supposed to be different — not one wherein people with information give it to those who don’t, but one wherein everyone has access to information while one among them (the teacher, of course) is especially good at navigating through it, understanding the gaps and tensions, pointing out the really productive points of inquiry. Now, says JSB, there’s no good excuse not to use this model with undergraduates and not just in graduate seminars. The general and remarkable access to information — a 24/7 proposition — should free instructors to focus on the really fun parts of teaching: the invitations to critical thinking, the fruitful interventions, the point-of-need support, the re-directions of attention, the due recognition of accomplishment.

In short, it’s not the technology that needs to change, but the teaching. And the change has already begun. What technology has done is enabled the change by being a transformative medium: not old wine in new bottles (because that’s boring) but something different because done differently. Students are likely to resist the change as much as some faculty — thinking is hard work — but the problems and solutions are pedagogical, not technological.

That, at least, is one way of looking at it.

What We Need Is What We Have (Part I)

October 6th, 2009

Telling tales out of school again: I was at a discussion of online learning at 80th St (CUNY Central) last Friday. We had been asked to read a much publicized, government-sponsored meta-analysis of studies of online and blended learning. In the press (the NY Times for instance), this had been billed as a study that (finally) showed online learning produced even better outcomes classroom-based learning, with blended learning proving better still. I could go into the skepticism the study has inspired, even among advocates of online instruction (see John Sener’s comment on the “good news,” for example), but I’m more interested in where we go from here. I think the premise of the meeting was that now, as never before, we ought to get going with online and blended learning. These alternatives are now established — and the institutional benefits are presumably transparent with enrollments spiking, new faculty hires hitting new records, and students ever more interested/acclimated.

Typically, I was interested in something else entirely. I’ve been doing faculty development for online/blended learning for a decade (and even a fair amount of “administrative development,” if you know what I mean), and so part of me was already feeling “been there/done that.” But I had also prepared for the meeting by looking into what else I might find that was useful. I had read, in addition to the study, recent surveys of online instruction’s growth like the latest annual Sloan-C survey. One point of interest was that, now that an article of faith was established fact (as studies go, anyway), there was still such resistance to online learning, registering as strong doubts about quality, especially from faculty. (A pretty compelling example of the genuine fear online learning inspires in faculty appeared in the Chronicle of Higher Ed a couple weeks ago as “The Dystopia of Distance Learning.“) And slowing growth belied the turned corner. It had been decelerating even as evidence of successful outcomes had been gaining steam. Now, according to some, it was even stalling. That was in fact what one maven had said in a Reuters release the day before the meeting and picked up by publications like USA Today:

Richard Garrett of Boston consultant Eduventures Inc. said interest in online education may have plateaued for now, awaiting innovations that will transform the experience beyond screen imitations of the brick-and-mortar curriculum.

There seemed to be no intended irony to this appearing immediately under the heading “BELLS AND WHISTLES?” I suppose that was one of the things that made me take notice. For me, the ironies always pointed in the other direction. Who thought classroom teaching so wonderful that it should be the gold standard? Was comparability (or better) the great desideratum? Or should we look to reinvent instruction? When the printing press made teaching something other than transmission through an intermediary, it redefined the roles of clergy and academics. Are we due for another such redefinition?

If we are, I don’t think this can or will happen by awaiting some technological innovation we don’t yet have. And I certainly don’t think it will happen by doing all we can to make online courses the simulacra of classroom-based courses (what we used to call, in the old days, “course conversions”). What will make it happen? I’d like to leave that as a question right now. Even if all I’ve said thus far is mere preamble, and I guess it is, it’s also a lot to wade through. So I’ll give myself some breathing space (and others a chance to weigh in), and try to push this further in the next post.

How Open Is Open?

September 22nd, 2009

I have been struggling with others (“with” both in the sense “together with” and “at odds with”) on how open the CUNY Academic Commons should be. This is hard stuff.

Why? I realize, with some chagrin, that I do not embrace a wholly open conception of the Commons. I am against closed doors and gated communities — password protected sites, proprietary software circumscribing proprietary holdings — but I also resist the sense that anything goes. As I said to one colleague, how would we feel if the CUNY Academic Commons (emphasis presumably on the adjective) were swamped by bureaucrats or undergrads (looking for places to bureaucratize or socialize respectively)?

I don’t consider that a wholly rhetorical question. Enamored of the alternative space(s) for intellectual property created by the Creative Commons, I felt sympathy as well as trepidation when I read a mockery of its core values expressed in the now-notorious (and anthologized) “Letter to the Commons”:

We appreciate and admire the determination with which you nurture your garden of licences. The proliferation and variety of flowering contracts and clauses in your hothouses is astounding. But we find the paradox of a space that is called a commons and yet so fenced in, and in so many ways, somewhat intriguing. The number of times we had to ask for permission, and the number of security check posts we had to negotiate to enter even a corner of your commons was impressive. And each time we were at an exit we were thoroughly searched, just in case we had not pilfered something, or left some trace of a noxious weed by mistake into your fragile ecosystem. Sometimes, we found that when people spoke of ‘Common Property’ it was hard to know where the commons ended and where property began.

There is some mischief but some justice in such comments.

I would feel more vulnerable to the veiled charges of hypocrisy and elitism if I were a person of principles. I’m not. Like a good rhetorician (and latter-day Sophist), I regard everything as contingent: a product of the people involved, the circumstances at hand, the matters of the moment. Intention (that will-o’-the-wisp) does matter to me, and I think it should matter to the Commons. In our particular case, we have framed a mission statement, and we should be guided by it (or amend it if we choose not to be).

There we’re explicit that the Commons is primarily intended for faculty, and as a place to “to support faculty initiatives and build community through the use(s) of technology in teaching and learning”; the intention is to “nurture faculty development through sharing replicable materials and best practices.” (These are ambitious goals, but they are also clear about not trying to be all things to all people, an ambition I don’t have.)

I think invoking the mission statement helps us in other ways: that its first words are “The Academic Commons of The City University of New York” justifies our requiring a CUNY email address for those who log in and post. The emphasis on the core mission of the University, teaching and learning, also helps to set (admittedly flexible) boundaries on the use of the Commons by students, administration, and staff, hedges against such admittedly far-flung scenarios as its getting swamped by undergrads or bureaucrats.

I do not think there is a contradiction between being a public site and having an intended audience. That may mean we are not absolutely open, but I then I don’t believe in absolutes.

A Conspiracy of the Willing?

September 7th, 2009

The ubiquity of information, combined with what’s happened in the economy (an economy that, like Monty Python’s flying sheep, did not so much fly as plummet), has spurred another round of discussions around what teachers (and colleges and universities) are good for. Drew Gilpin Faust’s “Crossroads” piece in the New York Times — “The University’s Crisis of Purpose” — is an example, one that tries (strains?) to rise above utilitarian demands to articulate a higher calling for institutions of higher learning. Yes, goes the gist, a college education is important for getting a better job or income and also for keeping up with Joneses — especially the Joneses (whatever their names actually are) in Europe and Asia — but a college education is so much more than that. So it’s said. But not very well. We are so lame about saying what that “more” is. Less lame or at least time-honored attempts — notably Newman’s Idea of a University — would sagely note the effort has been going on forever (in Newman’s case, as justification for borrowing from “pagans and unbelievers” and even Protestants).

Something similar happened when open education and/or online education got a lot of supposedly smart people struggling to say what the role of the instructor is or should be. And we’re in another such cycle. One listserv I’m on has noted that the upswing in enrollments and the downturn in the economy have made online instruction the “cutest kitten on the block” right now. With everyone from Arnold Schwarzenegger to Barak Obama touting online education, reporters are once again asking what the prospects are for some kind of turned corner. While important steps like Cape Town Open Education Declaration seem not to be on their radar, ventures like the University of the People are, and so some are asking why we need to bother with bothersome things like accreditation. Inevitably, when they hear of PLEs and the like, they ask if we even need to bother with the instructors.

I always have some dread of as well as interest in the discussions that ensue. There’s lots of talk about the importance of making sure students pass muster — the instructor-level equivalent of the utilitarian issues Drew Gilpin Faust was trying to get beyond at the institutional level. But we weary quickly of talking about instructors as enforcers — too uncool — and that’s when things get really bad. Out come the ineluctable phrases “sage on the stage” and “guide on the side” — directly connected to my gag reflex at this point — and there’s something already shopworn about the variants like ” sage on the side” and “guide on the stage.” Again, we’re struggling with things we’re not very good at articulating — often, I guess, because we’re being too generic and general.

What we too often don’t get into is how invested we are in what lies behind the notional terms “course” and “instructor” and “student”: so much cultural baggage and historical weight and institutionalized investment that we don’t have to worry about any of them going away soon. We can talk all we want about “communities of practice” and their importance to learning while forgetting that they usually don’t need to be set up. They are so vital that they are almost always already there wherever learning is going on. There are exceptions, I suppose, but I also suppose that to be a really effective autodidact you have to have an intelligence on the order of someone like George Eliot.

So what happens when you stumble into situations where you have real (social) learning going on without a “course” or “instructor” or “student” — where, moreover, there are no established alternative structures (e.g., apprenticeships) or even communities (peer/practitioner networks) because the practices are so new?

That’s a situation I think we now face in open education and online learning resources to some extent, with the great shining example (my favorite, anyway) being the CUNY Academic Commons. Still in beta, but due for general release very soon, it has to open itself up to what you might call “community formation”: groups will have to define themselves on the Commons, both practically and conceptually. Some are pre-existing communities of one kind or another, while some are groups just trying to get started. A representative of one of the latter wrote me over the weekend and asked, essentially, who would set that group up. I wrote back to say, essentially, that the Commons was a platform, not a service, but I and others would be willing to help with specific questions.

However inadequate that response might have seemed to the person I was replying to, it represented a leap of faith for me. It’s not as if I only imagine those “others”: there are people I could name right now. The problem is they are already people who have done the lion’s share of the work on the Commons, people approaching burnout. The activity they generate/bear represents an example of Clay Shirky’s power law distributions — as he puts it, “Diversity plus freedom of choice creates inequality, and the greater the diversity, the more extreme the inequality.” Those who accept more responsibility for the Commons, for instance, are going to do so much more than the larger number who want to tend their corner, or to lurk. And that’s fine.

But maybe we could broaden that A-list of people who welcome others, offer help, or share how they set up a group with a group in formation. I wouldn’t want this to be a call for more “leadership” — such a loaded term. And this would be more subterranean anyway, as befits an online resource. Here it’s not a matter of commanding the spotlight or the megaphone but of reaching out in quiet touches, individual contacts with new arrivals, correspondence across groups and areas of interest. It would have to be motivated by willingness. I guess what I’m hoping for a vast conspiracy of the willing.

A picture is worth … ?

June 15th, 2009

Alternative title: Block That Metaphor

I’ve been working on a presentation that is supposed to give some sense of our own dear CUNY Academic Commons to the outside world, and I have to have the requisite visuals. I thought it might be worthwhile to give folks a sense of what I came up with, though this was with more than a little help from Matt Gold et alia.

First, I wanted to show what the Commons is not. Well, not altogether, anyway. There were competing conceptions that did not quite capture all that we wanted the Commons to be.

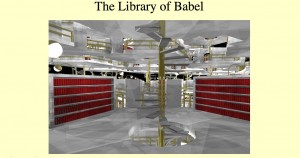

Competing Conception #1: A Repository of Stuff. For that, I came up with

and, because Borges’ piece is very much about endlessly receding taxonomies (“To locate book A, consult first book B which indicates A’s position; to locate book B, consult first a book C, and so on to infinity …”), also this:

Few things could suggest, better than these paired images, that the twin challenges of categorization and location for such a “repository of stuff” are dizzying. But if that conception is not the “right stuff,” neither is the whole-hearted focus on social interaction.

Competing Conceptions #2: The Gathering Place, the Agora, the Hub

It’s not enough to bring people together. Even and especially if you do manage to do that, you may only have a crowd.

Sunbathers at Manhattan Beach

Too much lollygagging? Maybe. Alternatively, I pictured it as part marketplace, part traffic jam.

Hyderabad Traffic and Market

The Commons is not (or not just) a place to come, hang out, interact. This is a more contemporary conception than a static repository, but it does have the enormous challenge of getting people to come and also structuring that activity without getting in the way of it. The watchword for such sites is often “If you build it, they won’t come” — and then what are you going to do?

Well, you could go organic. What these conceptions don’t take in is notions of growth, development, evolution — each a different way of framing the summum bonum of what we wanted the Commons to be and have.

Better Metaphor #1: Roots and Branches. Matt sent me this picture of a well-rooted tree as a possible image for the Commons:

Roots, roots everywhere

Lots of roots, but just one trunk — which reminded me that a stand of trees is often a clonal colony, that tree roots can beget new trunks in rhizome-like fashion. The great example is Pando [from the Latin for “I spread”] — aka the ”Trembling Giant” of Utah (a clonal colony of aspen trees with an interconnected root system that may be the world’s largest organism). I found a picture of those aspens on Wikipedia:

These Quaking Aspens may quake and tremble, but we probably want a better suggestion of activity than that.

Better Metaphor #2: The Beehive.

Matt also sent me Jim Groom’s post “WPMu as Beehive,” which featured this image.

That, strictly speaking, is not a beehive but a honeycomb — though what better visual way to drive home the point that you could have an organic image/metaphor that foregrounded storage? What I wanted was just such an image, but with some activity in it — some busy bees:

The idea of the beehive is especially useful because it helps to stress that, if you feel forced to choose between the repository and the hub of activity, you’re submitting to a false disjunction. As the beehive reminds us, you can have your storage and your activity too, your honey and your buzz. Social networks are about stuff as well as interaction. Facebook has become the largest collection of photos in the world, for instance. What might a Facebook for academics become?