Divining Madness

October 2nd, 2012

The annual “special section” on online learning done by the Chronicle of Higher Education is out, and it’s (almost) all about MOOCs. The cover proclaims “MOOC Madness,” and the big article is “MOOC Mania.” How apt. I used that same title a couple of months ago in voicing my skepticism about all the hype , and have had cause to return to that theme again and again. Now the validation given to this fringe phenomenon by the popular press makes me feel, if only for a paranoid moment, like a voice crying in the wilderness. MOOCs have not only arrived; the juggernaut has rolled past — crushing any naysayer in its wake.

The annual “special section” on online learning done by the Chronicle of Higher Education is out, and it’s (almost) all about MOOCs. The cover proclaims “MOOC Madness,” and the big article is “MOOC Mania.” How apt. I used that same title a couple of months ago in voicing my skepticism about all the hype , and have had cause to return to that theme again and again. Now the validation given to this fringe phenomenon by the popular press makes me feel, if only for a paranoid moment, like a voice crying in the wilderness. MOOCs have not only arrived; the juggernaut has rolled past — crushing any naysayer in its wake.

But wait a minute. What the articles actually reveal is something less than a wholehearted embrace. I was naturally first drawn to Ann Kirschner’s sampling of a MOOC (something I’m doing as well). The Dean of CUNY’s Macaulay Honors College is in many ways the ideal student, trying something she actually envisioned years ago while forging Columbia’s Fathom. She’s already knowledgeable about the subject, pressed for time, yet genuinely interested, ripe to find the MOOC she tried a useful learning resource. But it’s far from an ideal learning environment, and she’s quick to point what’s missing: “There was no way to build a discussion, no equivalent to the hush that comes over the classroom when the smart kid raises his or her hand.”

Other authors are harder on the next big — and we do mean big — thing. Much, both positive and negative, has been made of Sebastian Thrun’s famous MOOC on Artificial Intelligence, which initially enrolled 160,000 students but saw only 20,000 complete it. Greg Graham, a writing instructor, doesn’t even mention the completion rate. He’s horrified by the sheer number enrolled.

Perhaps Thrun and others like him have made the classic mistake of valuing quantity over quality. Those huge numbers on their screens are clouding their judgment about what is wrong with our education system and what it will take to fix it. Like Wal-Mart, online education promises greater numbers: To hell with customer service and quality; we’ve got discounts!

This seems a little shrill, but it does, from another angle, explain the lure of MOOCs. Those sheer numbers seem an answer to the cost disease presumably afflicting faculty productivity. If we employ conventional methods, there’s no way, with the cost of everything (including faculty) going up, that we can produce more educational “product” more cheaply. So it’s easy to imagine the administrator’s version of Thrun’s now famous comment, “You can take the blue pill and go back to your classroom and lecture to your 20 students, but I’ve taken the red pill and I’ve seen Wonderland.” Wonderland, indeed. If you’re an university president, imagine the thrill of getting so much more out of that first-rate prof you’re paying that six-fiigure salary to by getting six-figure enrollments.

Dean Kirschner is right: “Let’s give this explosion of pent-up innovation in higher education a chance to mature before we rush to the bottom line.” Yet there is another kind of rush on, and of a very different kind. Last Friday the Wall Street Journal published a piece on “educational competitiveness” rankings that showed how investments in Asia were changing the global higher ed landscape — pushing China above Germany, for instance, and just below the US and the UK. China now has its own analog of the Ivy League — the C9 — and its formula for success is not that much different from that of the Ivies — maximum investment (in faculty) and maximum selection (of students).

Whether MOOCs are a giant step forward, this seems a giant step backward. Surely there has to be something between this resurgence of social Darwinism and the assembly-line anonymity of some MOOCs. Technology can be about intimacy as well as reach, and reach can take into account need, not just ability or merit. We don’t need to decide whether to accept or reject MOOCs — that’s premature. But we do need to decide how to modulate as well as realize the possibilities they represent, particularly so they can reach the kinds of students CUNY is committed to.

Change and Persistence

September 27th, 2012

My title might seem a crass reminder of the so-themed CUNY IT Conference in late November, and it is, but it’s much more about the thinking provoked by reading through the proposals submitted, something I’m doing with a dozen other raters. (We come up with scores independently, then compare notes.) The question is not just what persists but what’s worth investing in. The economy’s turning around, innovation’s resurging, and we need to think about what we need.

We could start with what Derrida called une réponse de Normand (a favorite strategy of his): saying what it is not. What won’t serve us well is mere trendiness, the sorts of things fixated on by the popular press. The one constant is that we’re awash in innovations with the lifespan of mayflies, particularly new devices (or new versions of old devices). This is not to say that these things don’t make a difference, that they aren’t important. But the latest take on the new iPhone is a good deal less important than having a mobile strategy.

That goes for teaching trends as well. I’ve probably said enough about MOOCs, though the latest turn in the conversation, manifested here and there, is that these massive open online courses might be good for textbook publishers as well as publicity. So we’re starting to see ways of making money on vast “free” courses, but the fact is that you are not going to change education a course at a time, however “mega” that course is, particularly if you don’t bring the faculty on board. You need strategies (like the flipped classroom) that affect teaching and learning much more pervasively and generally.

What you especially need in all this swirling ephemerality is a center that holds — and remembers. That’s why it’s so exciting that discussions are beginning around an institutional repository for CUNY, one that might not be the static stash of PDFs so many IRs are but something much more dynamic because linked to the activity of the CUNY Academic Commons. If we could devise a way to help faculty represent themselves and their work (possibly even work in progress or in sites of collaboration) through an IR, that could be a very exciting prospect.

For an inkling of what this might amount to (and a needed corrective to my snarky remark about static stashes of PDFs), see my July post on interesting work from the Digital Conservancy at the University of Minnesota. If we look to some of these more innovative models, there’s a chance for CUNY to leapfrog from the back of the pack to the front, from being one of the relatively few universities without an IR to a university redefining the possibilities for IRs. The Commons has shown a capacity to get out in front thus. We did it once. We can do it again.

And we have good reason. Venues for scholarly publication are at once shrinking (especially university presses) and expanding (especially for new, non-traditional forms and formats). Teaching innovations are proliferating, but so is the need to share them — and to separate the wheat from the chaff. Open pre- and post-publication peer review is becoming more widespread. CUNY faculty can look elsewhere for such innovations, but they would be so much better off if they had their own resources for vetting, sharing, and archiving their stuff. And so would CUNY.

More on MOOCs

September 10th, 2012

Beatrice Marovich’s Chronicle of Higher Ed article “Online Learning: More Than MOOC’s” (whence I got my image) appeared last week. It was so wonderfully lucid as a thoughtful, dispassionate answer to Mark Edmundson’s “The Trouble with Online Education” that I couldn’t say much more that “Read it!” — and that hardly justifies a blog entry. But the Chronicle has also been publishing more fretful musings about how MOOCs (massive open online courses) will be (or at least remake) the future of higher education, and I can’t let that pass without comment.

Beatrice Marovich’s Chronicle of Higher Ed article “Online Learning: More Than MOOC’s” (whence I got my image) appeared last week. It was so wonderfully lucid as a thoughtful, dispassionate answer to Mark Edmundson’s “The Trouble with Online Education” that I couldn’t say much more that “Read it!” — and that hardly justifies a blog entry. But the Chronicle has also been publishing more fretful musings about how MOOCs (massive open online courses) will be (or at least remake) the future of higher education, and I can’t let that pass without comment.

The immediate provocation is Kevin Carey’s “Into the Future with MOOC’s,” whose very title is in its own way as eloquent as Marovich’s. While hers reminds us — and I hope we do not need much reminding — that almost all of what is now offered as online instruction is much more intimate and integrated than the vast but rare anomalies called MOOCs, Carey has seen the future, and he knows it is very different from what we know now. He promises that “the MOOC explosion will accelerate the breakup of the college credit monopoly.”

Both pieces are anchored in personal experience, but in tellingly different ways. Marovich tells of how, laid up by an injury, she came to online teaching reluctantly and was surprised by how empowered and connected she and her (regular-sized class of) students felt in the new medium. Carey tells of an awful learning experience he had as a student, one in which his term-long absence in a huge traditional lecture course went unnoticed but some cramming for the final got him a C: if he got credit for that, why not give credit for MOOCs? That’s like noting that human beings can survive in the polar wastes and then concluding they should settle there.

But wait: that’s going too far. MOOCs are not the problem. As I was at pains to point out in my long post on MOOCs, some MOOCs are entirely estimable teaching and learning experiences. The real problem for those who think MOOCs are going to remake higher ed is something the acronym apparently lets them forget: a MOOC is just a course (and not a course of study). Just in case it’s not immediately apparent, Jason Lane and Kevin Kinser ask and answer the question “Will MOOC’s Take Down Branch Campuses? We Don’t Think So” by putting it this way: “It is one thing for a student to pursue a course or two in an area of personal interest. But this is much different than taking the dozens of different courses required for a degree.”

As I read that, I felt a muted echo of something I read many years ago. I finally realized it was from Chapter 8 (“Re-education”) of John Seeley Brown and Paul Duguid’s masterful book The Social Life of Information (2000). That book, significantly, was essentially an attempt to explain why almost all the visionary prophecies of the nineties about the Internet had failed to come true. Those prophecies were memorably summed up in the “6 Ds”: demassification, decentralization, denationalization, despatialization, disintermediation, disaggregation (p. 22). Carey, in speaking of the “breakup of the college credit monopoly,” is a latter-day prophet of Internet-induced disintermediation. It’s interesting to see how Chapter 8 of The Social Life of Information (p. 215, to be specific) asks and answers whether that will be the fate of university instruction:

Will the university crumble into individual buyers and sellers? After all, you can buy books brimming with knowledge. (Indeed you can even buy credentials and finished college papers.) Why can’t these markets develop to replace the cumbersome university as information provider? Why won’t people just buy and sell knowledge across the ‘Net?

The answer, of course, is that knowledge doesn’t market very easily. As we noted in chapter 5, it’s hard to detach and circulate. It’s also very hard for buyers to assess. Indeed, people attempting to buy knowledge in one form or another often face a curious dilemma. If they can evaluate it, they probably don’t need it. If they need it, they probably can’t evaluate it.

Essentially — and in it’s entirety the argument is the best that could be made for why a baccalaureate should be 120 credit hours — Brown and Duguid are saying that what matters is the outcome of a sustained and complex process that produces an incalculably affected and complex product. It wasn’t readily acknowledged then, or now, because we have become so good at fragmenting and compartmentalizing knowledge into discrete units called courses. But what that breakdown is missing is what is really valued: the product of the enriching interactions (and checks and balances) of a sustained program of instruction, with all the socialization that requires.

Of course, it takes only a moment’s thought to realize that talk of MOOCs being a “Campus Tsunami” misses the point that courses are just courses, with or without credit, and there is a reason we deal in curricula as well, in majors and minors and gen ed and all that it takes to get into college in the first place. Saying MOOCs will replace the college experience is like saying some breadsticks will take the place of a multi-year meal plan. Let’s not confuse appetizers with sustained sustenance, or PR with education.

A Work in Progress

August 30th, 2012

The Chronicle of Higher Ed released its annual Almanac this week, an omnium gatherum of data on colleges and univeristies, and the data on matters technological is gathered here. Quite a lot of it is pulled from other gatherings of data, notably the EDUCAUSE Center for Applied Research, or ECAR, which does its own annual study of undergraduates and technology, including a survey of the students’ sense of how much (and how well) faculty use technology in teaching. The upshot is that we should not be misled by all the talk (hype?) about change and transformative practices. Yes, there are MOOCs (here and there), and they are getting lots of attention. “The reality, though, is that professors have been slow to reshape their strategies.”

The Chronicle of Higher Ed released its annual Almanac this week, an omnium gatherum of data on colleges and univeristies, and the data on matters technological is gathered here. Quite a lot of it is pulled from other gatherings of data, notably the EDUCAUSE Center for Applied Research, or ECAR, which does its own annual study of undergraduates and technology, including a survey of the students’ sense of how much (and how well) faculty use technology in teaching. The upshot is that we should not be misled by all the talk (hype?) about change and transformative practices. Yes, there are MOOCs (here and there), and they are getting lots of attention. “The reality, though, is that professors have been slow to reshape their strategies.”

For all the press attention given e-books, they account for only 1% of college bookstores’ revenue. Courses using lecture capture continue to increase, but even at places where they are peaking — public universities — the percentages are still in the single digits. Speaking of publics, more than half of those same universities are reporting a cut in their technology budgets for the third year in a row, according to the Campus Computing Project. The CCP also reports that Blackboard’s dominance has declined a bit — dropping from 57% to just over 50% — while one of the most interesting corresponding gains, if slight, is in the proportion of schools that have “no campus standard.”

Students are a little less than wowed with the technology they do see used in teaching. According to that aforementioned ECAR study, fewer than a third think the use they see is effective when it comes to clicker response systems, gaming devices, webcams, television (and recorded video), music devices, tablets, cameras, and smartphones. They seem to have the highest regard for WiFi, perhaps because they rely so much on their own devices, with nearly 90% of them having their own laptops, and pushing that particularly (a particularly powerful) device into the realm of near ubiquity.

Probably none of this is surprising, and it all seems to add up to the familiar two-steps-forward-and one-step-back shuffle. It ought to chasten, at least a little, those who talk abut academic technology in terms of campus tsunamis and restructured systems. There is no done deal, no silver bullet, no killer app. The next big thing is just another thing, and there are more of them all the time. Festina Lente (“make haste slowly”) is — or at least ought to be — our motto. We are a work in progress.

Acceptance, Angst, and Ambivalence

August 24th, 2012

A new report on faculty attitudes regarding technology is out from the Babson Survey Research Group and Inside Higher Ed — a follow-up to the report they released in earlier this summer (and I reviewed in a blog entry back then). Both reports mine the same survey, so the information here is not new, just more granular. And while the former report’s title, “Conflicted,” captures the mixed feelings faculty have (and especially the different responses different members of this very diverse group have to a number of different technology-related issues), this report’s title flatly declares them “Digital Faculty.” Is that a fair description? Not yet.

A new report on faculty attitudes regarding technology is out from the Babson Survey Research Group and Inside Higher Ed — a follow-up to the report they released in earlier this summer (and I reviewed in a blog entry back then). Both reports mine the same survey, so the information here is not new, just more granular. And while the former report’s title, “Conflicted,” captures the mixed feelings faculty have (and especially the different responses different members of this very diverse group have to a number of different technology-related issues), this report’s title flatly declares them “Digital Faculty.” Is that a fair description? Not yet.

Titles, of course, can only say so much, and the report itself details some telling points of conflict and divergence. Accentuating the positive, the overview in Inside Higher Ed says, “In general, professors are pro-digital.” But the devil is in the details, and even in some of the broad strokes. Faculty are more fearful than excited about the growth of online education generally; ditto the growth of online outlets for scholarship. What’s more, this report breaks out gender differences, and it shows that women report doing more online but also feeling more stress. Cathy Ann Trower, director of the Collaborative on Academic Careers in Higher Education at Harvard University, says this makes sense, that “women often feel more compelled to be immediately responsive to students and colleagues than men do.”

Trower’s take provides an interesting angle on the results: if faculty are in fact “digital faculty,” it may be more a reluctant acceptance of change than an enthusiastic embrace. The survey’s key strategy — to ask whether faculty are fearful or excited about different uses and manifestations of technology (and to insist on a choice of one or the other) — does not allow us to know about gradations of feeling. We can only infer, as Trower did.

Some things the survey results do make clear. Since the survey was done of administrators as well as faculty, we can see these two groups seem to see things differently. Administrators consistently overestimate faculty use of technology, particularly the use of any learning management system (LMS). As I. Elaine Allen and Jeff Seaman, co-directors of the Babson Survey Research Group, note, “Administrators perceive a much higher degree of faculty use of LMS systems for every dimension than faculty actually report.”

On the other hand, many of the results do justify the “pro-digital” claim. While faculty are more fearful than excited about the growth of online education, more than 70% are more excited than fearful about the growth of hybrid or blended instruction, and almost that many feel that way about the “flipped classroom” — the use of technology to offer instructional content so that instructors can spend less class time lecturing and more time interacting with students. Most also feel positive about the growth of online educational resources (OER), as they do about the growing use of OER and e-textbooks to replace traditional textbooks.

Still, the results of the survey, mined more thoroughly in “Digital Faculty” report, underscore the ambivalence of the report titled “Conflicted.” Part of it could be that faculty, if they are “digital faculty,” may feel themselves more defined that way than defining themselves that way. (Issues of agency, like gradations of feeling, are not easily gleaned from the survey results.) And uncertainty as well as ambivalence has to be a part of any thoughtful response to change. The sentence in the Inside Higher Ed article that really struck me as this one: “Asked for their gut reaction to the emergence of ‘outlets for scholarship that do not use a traditional peer-review model,’ 64 percent of professors said it mostly filled them with fear.” If “fear” is the right word there, it would be mostly fear of the unknown or at least unsettled, and that will be with us for a while.

The Right Foot

August 22nd, 2012

Despite the literalness of the image, I’m really thinking of this as “getting off on….” That’s a good thing to think about at the start of any term, and with the growing use of online discussions, there’s also evidence that there’s a clear way to do that. I’m ordinarily as cynical about “big data” as the next person — not that it can’t tell us a lot, but we’re not especially good at gathering and analyzing it just yet. Anyway, a recent entry in the Chronicle of Higher Ed‘s “Wired Campus” blog gives results of a just released study of online discussion forums (fora?) in 3,600 courses at 545 institutions of higher ed.

Despite the literalness of the image, I’m really thinking of this as “getting off on….” That’s a good thing to think about at the start of any term, and with the growing use of online discussions, there’s also evidence that there’s a clear way to do that. I’m ordinarily as cynical about “big data” as the next person — not that it can’t tell us a lot, but we’re not especially good at gathering and analyzing it just yet. Anyway, a recent entry in the Chronicle of Higher Ed‘s “Wired Campus” blog gives results of a just released study of online discussion forums (fora?) in 3,600 courses at 545 institutions of higher ed.

Some of the results were neither clear nor compelling. It turns out that students are much more likely to shroud themselves in anonymity when asking questions at “highly selective universities” than at other kinds of schools, which is somewhat surprising. (Is the idea that smart students thinking asking questions makes you look dumb?) But so much depends on how discussions are set up and configured, how different schools and classes and profs use them, etc. that it’s really hard to conclude much of anything from this particular datum.

More interesting is discovery that students who were asked to introduce themselves in online discussions posted two and half times as often throughout the term as those who weren’t. People who use discussion boards have long believed in the virtue of “icebreakers”: students say who they are and where they’re coming from at the outset. Everyone likes to talk about themselves, so this is not hard to get going, and the instructor gets a good gestalt of the class — prior knowledge, communicative skills, attitudes toward the subject, etc. Though I guess we must always recite the litany that “correlation is not causation,” here we have confirmation of what always seemed good practice. For why, there seems no better observation than that of Jim Groom, formerly of CUNY and now of U of Mary Washington; he said, in another article in another publication ( “The Intersection of Digital Literacy and Social Media” in Campus Technology), “A big part of digital literacy is understanding what it means for other people to see, experience, and find you online.” Groom is obviously talking about much more than a self-introduction in an online forum, but it’s a start. A good start.

Uneasy Equations

August 16th, 2012

The Commentary section (pp. A19-20) in the latest issue (8/17/12) of the Chronicle of Higher Education features two well-intentioned articles: “Don’t Confuse Technology with Teaching” and “Why Online Education Won’t Replace College — Yet.” There’s a fair amount of sage stuff in each, I guess, but I’m struck by why anyone would feel the need to read (or write or publish) articles so titled.

The answer is not far to seek. Both articles begin by talking, not about online courses or tech-mediated teaching generally, but about MOOCs (massive open online courses). Here we go again. As I tried to indicate in an earlier blog entry, MOOCs are hardly representative of online instruction. On the contrary, they are anomalous. Tried by some elite colleges with massive endowments, most of them neither requiring tuition nor offering credit, they nevertheless have some saying they will change the “business model” of higher ed (particularly those trendologists who can’t use “technology” unless it’s modified by “disruptive”); most students who take such courses don’t complete them, and they touch such a small part of the college-going population that they can’t be said to have any significant impact, except by grabbing headlines.

Still, they must be critiqued by some because they are hyped by others, and I guess I’m caught up in this myself. But what really bothers me is the way MOOCs are suddenly a kind of synecdoche for online or tech-mediated instruction, as these articles indicate. Remember synecdoche? — the figure of speech where a part stands for a larger whole? It’s interesting that, when I check Google for definitions of synecdoche, the first three (Wikipedia, Dictionary.com, and Merriam-Webster) all use the example “fifty sail for fifty ships.” This works only as a quaint recollection of a time when most large sea-going vessels had sails; as an example of synecdoche, it’s also unrepresentative of current reality, an archaism.

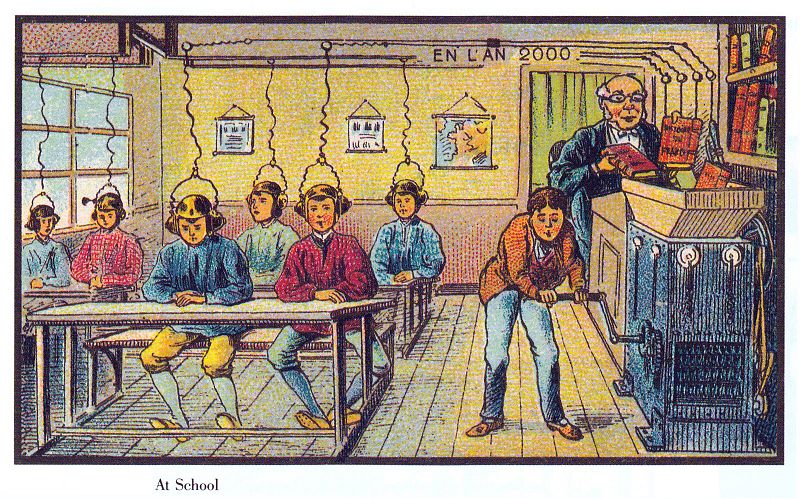

The equation of MOOCs with online instruction spins the other way, to some sort of fantasy or science fiction view of college instruction where students get what they need in largely unsupervised brigades. This dystopian vision is a variant on the approach of Gradgrind, Dickens’s powerful and enduring personification (in Hard Times) of the view that education is basically a content dump. (“Thomas Gradgrind now presented Thomas Gradgrind to the little pitchers before him, who were to be filled so full of facts.”) A French artist over a century ago nailed the ridiculousness of this take on education in an image:

College faculty know better than to think teaching and learning work this way, and so they should know better than to think online education (the anomalous MOOCs excepted) is anything like that. In the meantime, it apparently needs to be said that an imperative like “Don’t Confuse Technology with Teaching” is about as, well, imperative as “Don’t Confuse Your Kitchen with Your Dinner.”

Reading Unbound — or Rebound?

August 10th, 2012

It was pointed out to me that my last blog entry (on what we need to know about how we and our students are reading) left out any mention of the one big knowable among the unknowables: that our students are paying way too much for textbooks. True. So it seemed providential that today’s Inside Higher Ed had a piece on free textbooks titled Textbooks Unbound.

The punny title was one way of signifying that the article focused primarily on Boundless (“The Free Textbook Replacement”). And the ambiguity of that parenthetical (does it replace textbooks for free? or does it replace free textbooks?) is also significant. Unlike purveyors of free textbooks like Flat World Knowledge or the Community College Open Textbooks Collaborative, Boundless starts with what instructors want from a textbook and aggregate that from what’s out there. Given the growth of open educational resources (OER), that’s a lot, but it’s also a lot to look for (or look through), hence the utility of something that pulls these things together and packages them.

As the article in IHE points out, it’s also another kind of threat to the standard business model for textbooks, sort of the second swing in the 1-2 punch. Giving whole textbooks away is one thing, but when you start pulling stuff together (including multimedia, things that go beyond what you can find in a standard text), that creates real problems for publishers. The article is really on the stir that has resulted from publishers crying foul, and especially the federal court complaint filed by such major players in the textbook publishing industry as Pearson, Cengage, and MacMillan. Ironically, because Boundless uses open content, the suit charges that it’s ripping off the structure of existing textbooks, filling them with freely available content but retaining (borrowing?) a form that students and instructors are used to. And the real irony is that this repackaging that retains the package’s traditional shape comes from giving professors what they (supposedly) want: the same old same old, only without the cost.

This seems to be that familiar shuffle of two steps forward and one step back: we have free content that approximates what publishers have been (over)charging for, but in the same form. What transformed the music industry was a transformation of the way we experienced music, not just the way we bought it. Music was suddenly not just cheaper than formerly but more mobile, more find-able, more share-able. We didn’t have to buy an album to get the sought-after song. We didn’t have to search through used record stores to find that beloved old tune. It wasn’t just the price.

What if we similarly transformed the way we brought together and assigned content for a course? What if it wasn’t a matter of assigning one chapter after another? What if professors didn’t give students basically what they themselves were given at that age and stage, all pulled together in a compendium? What if students were able to choose and provide at least some of the reading? What if the discovery of it was part of the learning process? And what if only some of it was found and the rest made by the class?

Boundless has made a new move both the publishing industry and on OER, but there are lots of moves still to be made.

Getting a Read on Reading

August 8th, 2012

Both of the daily newsletters I get from the Chronicle of Higher Ed (“Academe Today” and “Wired Campus”) featured the same piece this morning: “The Digital World Demands a New Mode of Reading.” The title is unfortunate, especially in its use of the singular. More than anything, the article is about the proliferation of modes of reading (and modes in multiple senses: different formats, different kinds of attention, different processes, even different versions, in one person, of what one interviewee calls the “reading self”).

Though whole books are mentioned (The Pleasures of Reading in an Age of Distraction, Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain), the article is wholly anecdotal, and the anecdotes all contribute to the sense of multiplicity, variety, and (for me, at least) confusion. Alan Jacobs, author of The Pleasures of Reading, reads voraciously and omnivorously but seems to do nothing else. (One irony is that the one datum in the article that gets the most thorough explanation is who Channing Tatum is. Why? Because Jacobs has no idea, what with his reading regimen that proscribes all TV and movies.) Maryanne Wolf, author of Proust and the Squid, rereads Hesse’s Magister Ludi to see if she can discover her “older reading self.” (She can, she says, but why she would conduct this experiment by rereading — never the same as the first encounter — and choosing to read a book in translation [or in another language] is a puzzle.)

There are certainly plenty of books and articles mourning the changes to reading brought on by the rise of the internet. Sven Birkets’ The Gutenberg Elegies: The Fate of Reading in an Electronic Age, originally published in 1994, is probably the granddaddy. But they tend to be (very) personal takes on the issue that hardly tell us what is really happening to us and our students. We can have our suspicions and personal opinions, our pulse-takings and personal experiences, but what do we really know? What, as educators, have we ever really known about what happens when a chapter is assigned and students either get it (whatever “it” is) or they don’t? Is that even the right way to frame what we should expect to see happen?

The questions are important because of the move to what you might call guided auto-didacticism, particularly via MOOCs and online extension courses that eschew the sustained interaction of established online instruction (too labor intensive and costly, presumably) for a trading of content and exams. If one mode of learning on the rise is the 21st-century version of the correspondence course, where material is made available and then machine-scored exams determine whether the student “gets it,” we had better be a good deal clearer than we are about what “getting it” amounts to. That would mean being much clearer about the cognitive processing involved as well as the validity of assessments used — and much more concerned about that than the putative contraction of attention spans and increase in impatience and distractibility.

Conflicted

August 6th, 2012

“Conflicted” (full title: “Conflicted: Faculty and Online Education, 2012“) is the name given one of the two major survey reports released this summer on how folks feel about the impact, on higher ed, of technology generally, and of online learning specifically. It was co-sponsored by Babson Survey Research Group and Inside Higher Ed and was released in June. The other survey, released in July, is titled “The Future of Higher Education” and was released in July; it was co-sponsored by The Pew Internet & American Life Project and Elon University.

These are the surveys I mentioned at the end of my last blog entry. Together they paint an interesting picture of attitudes and prospects, particularly because both forced respondents to choose between opposing positions with no middle ground. As the authors of “Conflicted,” with their special attention to faculty attitudes put it,

Our experience in surveying faculty has shown that they are very good at providing well-thought-out and nuanced responses. They are less successful at providing unambiguous responses without qualifications. One question in the current study was purposefully designed to force just such a response; it asked, “Does the growth of online education fill you more with excitement or with fear?” Only two responses were possible: “more fear than excitement,” and “more excitement than fear.”

Nearly 60% — to be precise, 58% — of the faculty surveyed (over 4500, representing all types and classes of higher ed institutions) reported feeling “more fear than excitement.”

Interesting. Even more interesting is the way the other survey forced the same “choice of sides” in asking a more mixed audience what they thought things would be like in 2020 (and I quote from the survey’s own overview):

In the Pew Internet/Elon University survey of 1,021 Internet experts, researchers, observers and users, 60% agreed with a statement that by 2020 “there will be mass adoption of teleconferencing and distance learning to leverage expert resources … a transition to ‘hybrid’ classes that combine online learning components with less-frequent on-campus, in-person class meetings.” Some 39% agreed with an opposing statement that said, “in 2020 higher education will not be much different from the way it is today.”

Though their targets are different, it’s tempting to see a fearful symmetry between the two surveys, one that’s hardly counterintuitive (the more change perceived, the more fear generated). But that might be missing the point … about how the surveys might be missing the point. For why, let me (with your indulgence) quote again from Jonathan Rees”s essay “The Obsolescence Question,” featured in the blog entry just prior: “Personally, I go back and forth between optimism and despair about the future of my profession.”

That’s a position most of us probably don’t find weird or anomalous. Most of us can probably identify, maybe daily, with the alternating of hope and fear Rees articulates. That’s hardly a scientific survey, but it is a way of allowing an important point: that,given “the maturation of online education” (Rees’s phrase), an academic can regard the future of higher ed with profound ambivalence, oxymoron or not.

Though those recent surveys do register a strong sense of change in the air and skepticism — even fear — about its effects, it’s that ambient ambivalence that they miss.