The Story of MOOCs (Chapter 3.14…)

October 15th, 2013

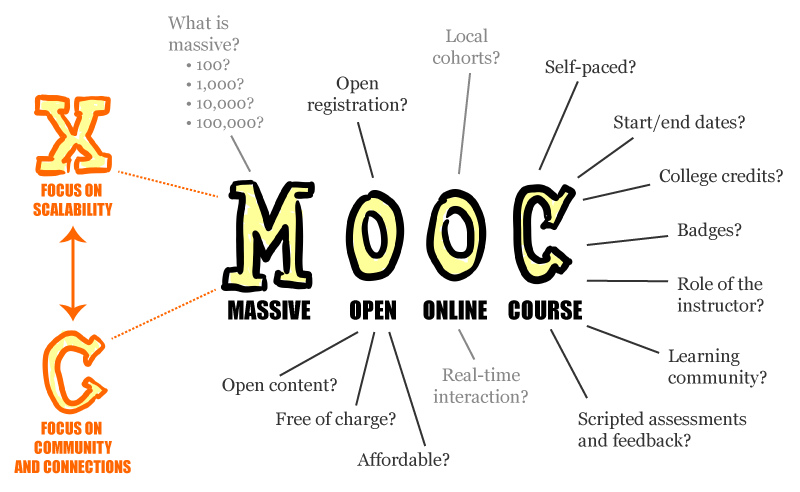

The story of MOOCs is not a single story. Once touted as higher ed’s own singularity, there’s nothing singular about MOOCs any more. They come in all sorts of shapes and sizes, openness and course-ness. And the point that they’re all over the place (in all senses) has been made ad infinitum. So why do we feel like we’re going around in circles about whether they’re a good thing or a bad thing (as if they were one thing)?

Some of this is the familiar pattern of action and reaction, so regular it has begun to feel like the tick tock of a pendulum. My last blog post — “Skepticism Abounds” — took its title from a report on a survey of faculty and administrators regarding online learning generally and MOOCs in particular. The same day, in the same source for that report (Inside Higher Ed), came a piece from the president of the American Council on Education (ACE) meant to be reassuring. Titled “Beyond the Skepticism,” it noted that there were indeed reasons to be skeptical, that “it hasn’t taken long in many quarters of our community for acclaim to accede to skepticism, and excitement about MOOCs to fade amid charges of excessive hype.” But not to worry: ACE will vet these MOOCs and decide which are worthy of credit. No sense here that faculty might be skeptical about that independent vetting — certainly independent of said faculty.

But the naysayers have their own organizations, and now they’ve gone “meta”– combining no fewer than 65 organizations into one coalition. No longer limiting their protests to a vote here (from the Rutgers faculty) and a letter there (from the San Jose State faculty), they have the Campaign for the Future of Higher Education. Its first report, subtitled simply “Profit,” warns against the entrepreneurial aspect of MOOCs and online learning, which got the attention of the Chronicle of Higher Ed, Campus Technology, and Inside Higher Ed. According to that last, “The report ties the current state of higher education to industries that have recently experienced economic downturns. The unregulated growth of ed-tech companies is described as a boom-and-bust cycle similar to the dot-com bubble that burst in the early 2000s, while rising student loan debt burdens and default rates are compared to the factors that led to the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis.”

That’s painting with a broad brush, but that’s done equally artfully by both sides. A defender of MOOCs, James G. Mazoue, promises to explode the “myths” about MOOCs in the latest EDUCAUSE Review, but as a counter-argument it’s really my-straw-man-meets-your-straw-man. The “myths,” framed as statements like “It’s All About Money” or “MOOCs Are Inherently Inferior,” are phrased as the kind of absolutes we’d know to mark False on a True-False test even if we knew nothing about the subject. Of course there exceptions to those statements, we think. In fact the real problem is that most MOOCs are themselves exceptions, one-offs and stand-alones, not curricula or integrated parts of a larger plan. Go ahead, just try to generalize about them. Or even try to frame expectations about them. Wait… Could that be a problem? Could that, right now, be the problem?

Problems or not, MOOCs were for so long (or at least loudly) framed as a solution, and there it really is all about money, even and especially if the O-for-open means both accessible and free. The problem is that higher ed currently works on an increasingly expensive and possibly unsustainable business model, especially in these days of shrinking public support. This is something William G. Bowen treats with remarkable candor in “The Potential for Online Learning: Promises and Pitfalls,” which appears in the same EDUCAUSE Review as Mazoue’s myth-busting article. What Bowen has to say on the subject is quite bracing — and worth quoting at length:

Faculty members understandably fear job losses, as Professor Albert J. Sumell, at Youngstown State University, cogently and sympathetically explains in an article aptly titled “I Don’t Want to Be Mooc’d.” Although there are ways of minimizing such risks of job loss (e.g., by redeploying faculty to higher-value tasks and by teaching more students), we have to be prepared to contemplate shifts in faculty ranks—both in overall numbers and in composition. We also have to recognize the implications of such possible changes for graduate education and for what is called “departmental research.” John Hennessy, at Stanford University, is one of the few leaders in higher education willing to be brutally candid in talking about such subjects.

The plain fact is that a combination of fiscal and political realities will continue to put inexorable pressure on the economic structure of higher education in the United States, especially in the public sector. Although an intelligent reexamination of tuition policies and financial aid policies can be of some help, I do not think there is any way to avoid thoroughgoing efforts to raise productivity—both by reducing the “inputs” denominator of the productivity ratio and by raising the “outputs” numerator.

Bowen really does explain something here: why the discussion of MOOCs and alternative modes is getting such attention — not least of all from administrators — even without solid successes or a proven business model. (Speaking of sustainability, giving it away is not a long-term option either, as everyone knows.) Costs are exceeding the power of institutions to control or students to bear. Change is already happening, in other words, and it is carrying away treasured ideas of equity and mobility. As the New York Times pointed out earlier this year, important studies are documenting the extent to which the educational gaps between the rich and poor are worsening, widening. MOOCs, especially in their current state — where so often the “sage on the stage” just becomes the “doc on the laptop,” as Cathy Davidson puts it — aren’t yet a fix, much less a cure-all. But they might be a crack in the wall. And the choice is not the false dichotomy between accepting or resisting change; the best choice, the third path, might be resolving to give it the right direction.

See also:

- CUNYfying Uses of Technology (December 5th, 2016)

- Both/And — or When You Come to a Fork in the Road, Take It (March 18th, 2015)

- The Problem(s) with Innovation (May 12th, 2014)

- MOOCs: Flame out or Flame on? (March 28th, 2014)

- Feeling Disrupted? (January 30th, 2014)

October 16th, 2013 at 9:44 am

But this starts off from a false premise. The “costs” of higher education are not really “exceeding the power of institutions to control or students to bear.” That’s a ruse. In fact the costs are increasing, because public support for education is being reduced. Vested interests are defunding public education so that “rising costs” can be used as an excuse for privatization.

October 16th, 2013 at 11:03 am

Well, yes and no. Not that I want to make Bowen’s argument for him (or that he needs me to), but, while he is very conscious of public defunding (it’s a major part of his argument), that’s not the sole cause of rising costs. Costs are rising because the cost of living is rising. And that creates a special problem for areas like the arts and education, one Bowen and a co-author it’s named after — see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baumol's_cost_disease — called the cost disease. It’s a function of capitalism that you need to make more and more on less and less, and this is easier if you’re making widgets (and can introduce means, technological or otherwise, of making them faster and cheaper), but if you are a violinist, for instance, you can’t introduce “efficiencies.” Even if public support remained stable, the costs of education would continue to rise. And so would the pressure to control them.